Thinking Strategically

A reflection on pre-emptive life lessons from competition, deal making, and auctions

1. Introduction

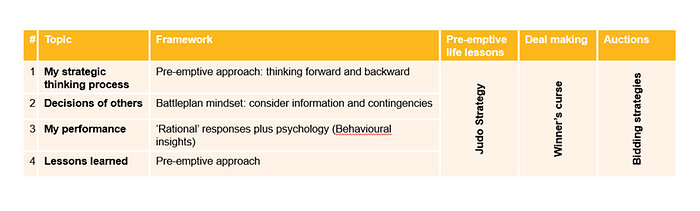

In this article I will reflect on three case exercises: pre-emptive life lessons on competition (Judo Strategy), deal making (Winner’s curse) and auctions (Bidding strategies). I selected these case exercises to analyse my experience because all three have a common theme — competing strategically — and the later two have the common theme competing under incomplete information.

For each exercise I will critically discuss first the strategic thinking process which I used to make my decisions, second the decisions of the other participants with whom I played the exercises, third my performance in the exercises, and fourth what I have learned in the exercises that I can apply in my career.

For the analysis I will use the following framework¹ of the Game Theory² extended by Behavioural Insights³ to think strategically on how to game competitors. First, I will use a pre-emptive approach to critically analyse my strategic thinking process in the exercises. I will review whether I thought forward and backward with both mind and heart to make my decision. In addition, I will use this approach to apply the lessons learned from the exercises to my business career. Second, I will assess whether I used the battleplan mindset in the exercises. By analysing whether I considered all information and contingencies to anticipate the decisions of others in the exercise. Third, I will examine whether I used both ‘rational’ strategic responses and psychology (Behavioural Insights) to assess my performance in the exercises.

2. Reflection on exercises

2.1 Pre-emptive life lessons on competition

We kicked the first Thinking Strategically session off with a breakout group discussion about pre-emptive life lessons on competition. In the breakout group we discussed my own experiences at one of the worldwide leading logistics and transportation incumbents. From my experiences in Corporate Strategy, we discussed strategic competition in the European rail market. In 2013 my previous employer faced the liberalisation of the European and German rail market.

2.1.1 During the strategic thinking process my Strategy group…

did not sufficiently pre-empt the competitive responses of other parties, specifically the market entry of the new bus operating start-ups.

2.1.2 The decisions of the new bus competitors…

to target the low budget segment like participants with low prices, led to the result that the bus companies quickly took over market share from my previous employer.

2.1.3 My Strategy team’s performance…

showed how we could have done better in hindsight. I came to the conclusion that the two main failures were not to anticipate competitive behaviour and then to pre-empt it⁴. First, the threat and market potential of the bus companies was not assessed correctly — maybe because of the incumbent’s overconfidence⁵. Second, when the company realised the market entry, they did not take actions against it, for example by offering to same low budget transportation for the participant target segment.

2.1.4 I have learned from the group discussion…

how the new start-up in the bus market competed with my large incumbent employer through the Judo Strategy⁶ — similar to how Freeserve overtook AOL⁷ in the Internet access market in 1999.

Judo Economics show how changing the competition game⁸ versus playing the game as well as creativity and credible commitment can be a successful strategy. Similar to Judo Strategy the value capture model (VCM)⁹ predicts the forgone value the company could have generated from transactions with other players.

The bus start-up employed several strategic principles from the Judo Strategy¹⁰ to win the competition against my incumbent employer. First, the start-up played the “puppy dog ploy”. That meant that the challenger kept a low profile with low budget transport services and avoided head-to-head competition on major transportation corridors of the incumbent.

Second, they defined a new competitive space, the low budget transportation for price-sensitive participants, and they learned to excel in that niche. The start-up showed that they understood the psychology¹¹ of their student travellers by accounting for the fact that they are emotional (Green, environmental-friendly busses), physically and cognitively lazy (Convenient online shopping experience) and influenced by context in ticket purchase decision-making.

Third, they follow through fast and moved onto the incumbent’s transportation corridors and into the business traveller target segment. Eight years after the market liberalisation they proof to be very good in what they do, long-term. The reason is that they offered coordinated switching incentives¹² to all three parties involved: players adding to the start-up’s benefits (Bus operating companies), channel players for early adopters (Online shopping), and adopters (Students).

Forth, the start-up leveraged my employer’s assets. They identified that my employer’s business unit Rail Transportation Network is their greatest liability. The significant investments in the rail transport network were a barrier to change. The bus challenger entered the market with a cost leadership strategy and low budget and dumping prices. The incumbent did not compete on these low prices until recently because of their high network fix costs.

2.2 Thinking strategically in deal making

In the following I will analyse the exercise “Acquiring a Company Case” — a bidding case in which a “competitor holds cards that you can’t see”. The case is related to common value auctions¹³ such as for oil-drilling rights. In this exercise I as the acquirer was instructed to acquire another company, the target, in a tender offer. The case represented strategic thinking in competitive scenarios with incomplete information, specifically deal making.

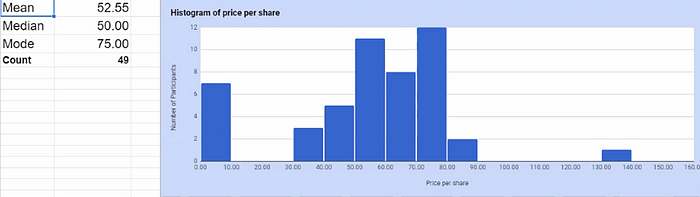

The value of the target company depended directly on the outcome of a major oil exploration project. This meant that the value of the company under the current management could have been between 0 and 100 per share. In addition, whatever the value under the current management, the company would be worth 50% more under management of the acquirer’s company. The target company knew the results of the exploration project when deciding on whether to accept my price offer. However, my company did not know the results when submitting my offer. The target company accepted only an offer that is greater or equal than the value of the company of its own management. The question was then what price per share I would tender for the target company’s stock.

2.2.1 My strategic thinking process…

to make the decision was that from the instructions I expected the average plus 50% to be the optimal price offer. I assumed that the company is worth the average of 50 share value under the existing management. Therefore, I calculated that it is worth 75 share price under my management. I assumed my bid of 75 share price to be profitable.

2.2.2 My performance in the exercise…

was in line with the decisions of the other participants. My performance resembles the standard outcome in common-value auctions. It tapped into the Winner’s curse and hubris¹⁴ because I won the bid for the target company in the tender but was likely to have paid more than the target was worth.

My bidding strategy of 75 share price based on the average was developed without the response of the current company to my bid. The problem was that the current company was likely to agree on that bid, if the target would have been worth more than my bid. The target company would only accept my bid if the true worth of the target was at the lower end of the range in between the average of 50 to 75 share price. The explanation was that with my bid amount of x, my bid would only be accepted by the target company if it were worth between 0 and x under current management.

The company would be worth x/2 on average if my bid were accepted. That meant that under my management the average worth was 50% more than the current worth: (1.5) (x/2) = 0.75x. Consequently, the target company would only accept the bid when my bid is overvalued because the value under my management of 0.75x was always less than x.

2.2.3 I have learned from the exercise…

that competing strategically with incomplete information in deal making means that it is crucial to take the Winner’s curse¹⁵ into account in my bidding behaviour. Otherwise, I would expect to lose substantial amounts (see calculations above for bidding). To generalise, in such common value auctions, I would win only when I have overpaid and therefore failed to pre-empt the winner’s curse.

In my Strategy career, I can apply the learnings to overcome the systematic biases¹⁶ in the way humans think such as the Winner’s curse which are undermining the M&A activities in the group.

For the bidding phase in future M&A transactions, I have learned that to set a limit price and avoid bidding wars avoids the Winner’s curse.¹⁷ Studies showed that successful acquirers are more likely to exit when their competitors initiate bidding war. That means that 83% of the rewarded companies withdraw at least sometimes the bid, compared with only 29% of unrewarded company. Consequently, I will recognize the red flag when competitors enter the biding and will evaluate whether to drop out of the bidding.

As one mitigation strategy, I will use incentives to avoid the Winner’s curse for my group. I will implement for my team to tie the compensation of my employees responsible for the deal’s price to the success of the deal. The measurement could be for example percentage of estimated synergies realized.

At my senior management’s side, I will lobby for another mitigation strategy, to have a dedicated M&A department. These changes to the environment and context of the employees (Nudging)¹⁸ can influence the behaviour to pro-actively generate an alternative to the current M&A deal and in addition to sets a price limit for the deals — without restricting their freedom of choice. In addition, even though our maximum price might be higher than target’s true value, but the strategy could prevent our group from entering into a form of auction fever; this meant increasing the bid above the level we initially set as prudent. The process would be that the firm recognizes the red warning flag and stops negotiating when the acquiring firm’s limit price changes during the bidding process. The acquirer should be struck by a red flag if the acquiring firm does not have a limit when it starts bidding.

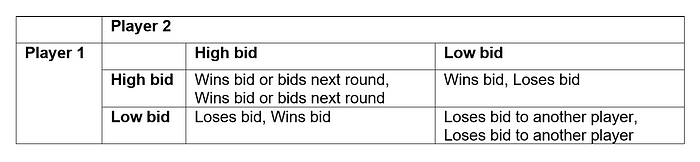

2.3 Thinking strategically in auctions

The second exercise which I will analyse are two different auctions. An auction is a case when “every player holds cards that others can’t see”¹⁹. In the simulation we played two types of auctions: first the English with an ascending bid and second the Dutch auction with a descending bid²⁰. In both auctions the auctioneer auctioned a ‘token object’ and each participant has been informed about their redemption value V for the object. The rules were set that the participant who wins the object paid the auctioneer his or her bid r, was paid his or her redemption value by the auctioneer and earned the difference (Redemption value minus bid = (V-r)).

2.3.1 The strategic thinking process I employed to make my decisions…

was based on the fact that both the English and the Dutch auction are private-value auctions²¹. In private-value auctions, the optimal bidding strategies²² including decision when to shade down bids from the bidder’s true valuation depend on the auction type used.

English auction

The optimal bidding strategy in the standard English auction was straightforward given that I know knew my valuation. My redemption value was 6 pounds. Consequently, I followed through my strategic thinking process that my bid should be a little bit below 6 pounds for the English auction. This would allow me to win the bid by going to relatively high price but still make a profit.

Dutch auction

The Dutch auction started from 18 pounds and then descended by 50 cents. My valuation was again 6 pounds and therefore I calculated my bid to be slightly below 6 pounds to still make a profit.

2.3.2 The bidding decisions of the participants…

English auction

with whom I played in the exercises influenced my biddings. I soon realised that the last ascending bid of 7 pounds made by a rival bidder was above my own valuation of 6 pounds. Consequently, I was not willing to bid higher and I did not concern myself with any further bids.

The results of the bidding were 14 pounds for the highest bid and then 13 pounds and 11 pounds. The bids of 13 and 11 pounds were errors because the bidders exceeded their redemption value of 10 pounds (r). The one participant won the bid by closing the deal at a bidding price of 14 pounds. This was the only participant who had a valuation of 15 pounds (V) in the auction. The rational was that if the last bids made by rival bidders (r) were still below the highest valuation V, the bidder with the highest valuation would have bidden at all.

Dutch auction

In the Dutch auction the decisions of the other participants influenced my bidding behaviour. When the price which was called out by the auctioneer was above my valuation of 6 pounds, I chose not to bid, considering my bidding possibilities. The deal was closed with a winning bid of 13.5 pounds. Because the winner had bid before the time the price got down to my valuation, I did not bid. Therefore, the participant with a bid of 13.5 pounds won the bidding as the bidder with the highest bid. This was the only person with a valuation 15 pounds (V).

2.3.3 My performance in the exercises…

was good because I understood the instructions and acted accordingly.

English auction

The participant who won the bid at 14 pounds did not perform the most efficient. The price that the participant with a redemption value of 15 (V) should have to pay by playing with two best competitors at 10 pounds (r) would have been 10.5 pounds. In that case, the bidder with the highest valuation should only have add a penny or 0.5 pounds to the rival’s valuations (r) and bid r plus 0.5 pound. The strategic thinking process should have given her the reasoning to only leave a bit of more money on the table than her best competitors to win the bid; if she would have known the redemption price of her best competitors — otherwise it would have been a risky strategy. The winner got a win for r and made an effective profit²³ of V — r. With a bid of 14 pounds, she only earned 1 pound instead of the maximised earnings of 4.5 pounds. This can be explained by the fact that she might have lost her mind or would not mind of losing budget.

The distribution of the redemption values was 15 pounds for only one person and 10 for two persons. Two other persons submitted bid of 11 pounds and 13 pounds in addition to the winner with her bid of 14 pounds. Consequently, these two participants bid higher than their valuation or budget maybe because they did not get the instructions right.

Another reason which is prevalent in real-life negotiations why a person submits a bid higher than their valuation is that bidding frenzy²⁴ might occur (Psychological function). This means that everybody tries to win and gets pumped up and therefore acts irrationally.

But bidding frenzy can also be a reason why auctioneers like to run English auctions; because this auction type reveals what everybody thinks the price should be. The ascending process of the bidding incites to bit higher and higher. Therefore, this auction type is good for products where value is not quite clear.

Dutch auction

For the Dutch auction, the distribution of the redemption values was the same: only one person with 15 pounds (V) and two people with 10 pounds (r).

When no one had bid by time price gets down to V the highest-valuation bidder chose to bid. He had two options: He could have bid immediately and earn zero profit or wait for price to drop lower. Waiting a bit longer would have increased the profit that he takes from that auction, but it also increases his risk of losing the win to a best competitor. Therefore, Dutch auctions can result in higher prices²⁵ than other auction types.

In general, the optimal bidding strategy comprises shading²⁶ the bid. Consequently, shading is in the interest of the winner. The winner decided to take the risky tactic to go down to 13.5 pounds. Nonetheless, the winner in this exercise confessed to have made a mistake by not attentively listening to the auction while congratulating the previous winner and therefore shading the bid to 13.5 pounds. Here it seemed likely that altruism and socialization²⁷ contradicted the Game Theory’s assumption to predict how selfish rational people will behave rational.

The precise amount of shading depends on a cost-benefit²⁸. Because the increase in shading — which means decreasing of the highest valuation bid from V — provides both an advantage and disadvantage²⁹, the bid of the person with the highest valuation would have been optimal when the last bit of shading just balances the following two effects: The shading increases the profit margin if the bidder wins the object but decreases the change of the player to be the highest bidder and consequently to win the bid.

This means that the tactic of the winner to go down bore the risk that if both valuations were close together, for example when another person was at 14.5 pounds and the winner at 15 pounds, then this rival bidder could have submitted a bid of 14 pounds and won the game.

2.3.4 I have learned from the exercises, …

first, the differences in competing strategically in Dutch versus English auctions³⁰.

English auction

In the English auction the winning bid hovers around the second highest valuation with 10 pounds or a little bit more. This means that in this type of auction the highest bidder gets the win for the valuation of the second-highest bidder. Therefore, the winner is only paying the second highest valuation (Single implication). How close the final price is to second-highest valuation is determined in the minimum bid increment defined in the auction rules (In this exercise 0.5).

Dutch auction

In contrast, the Dutch auction is more ambiguous. With a known distribution the winning bid is on average still the second highest. However, it depends on the risk aversity of the player. When the player would like to take on risk, he or she would let the price drop to 11 pounds. He would feel tense if another person has 15 pounds and therefore win the deal. If the player want be safe, he or she should just let the price fall to 14.5 pounds — only little bit below 15 pounds — and then bid. The difference between both auctions is that auctioneers get a higher deal price in a Dutch than in an English auction as result. In contrast, the English version has this psychological function³¹ that Dutch auction cannot quite produce.

If everyone knew exactly the distribution of the values, the winning bid will still be the second highest valuation and even in the Dutch auction the winner would be the second highest valuation.

In addition, the bidder with the highest valuation does not always win. In these auctions the highest valuation will win. The economists call this efficient.

Furthermore, the winning bid is sometimes not efficient. In some auctions the highest valuations are close to each other. If the person with highest valuation and tries to gamble in the Dutch auction and the person with the second highest valuation bids a higher bid earlier, the person with the second highest valuation will win.

Second, I have learned from the exercises the difference between price negotiation and auctions³². The auction is described as a formalised, mechanised version of the price bargaining. It is to state that both are ‘participative pricing strategies’³³. However, an auction is useful when the player is uncertain about the other side of the transaction and the value to gain is high enough in contrast to transaction costs.

Consequently, the decision to choose between running an auction or not should be based on the following criteria. In both the English and the Dutch auction, the winner should only pay the second highest evaluation.

Dutch auction

However, in the Dutch auction if the highest and second highest valuation is far enough from each other, the bidder with the highest valuation would leave a lot of money on the table by not knowing that the second valuation is far away and therefore bidding a lot higher than the second valuation. Therefore, if the auctioneer knows that one of the buyers has a much higher valuation then the auctioneer should negotiation with that person — the negotiation would be the better choice.

To sum up, the lessons learned from these exercises are that the buyer who values the second highest bidder the most actually has a much higher valuation than the buyer with a valuation close to the second highest valuation. If the former is the case, then the auctioneer should not throw an auction, because he or she will leave a lot of money on the table. The seller is going to sell an object, and the auctioneer knows that bidders really stand out with having like much higher valuation than everybody else. Then the auctioneer probably should start negotiating with that person trying to fix a price with all sort of tactics. However, he or she should not auction it off.

In general, the bid is quicker in the Dutch auction, but also more conservative because the auctioneer sells the bid at a higher price such as in the case of tulips.

3. Conclusion

To reflect on how my learning experience in this module can help me deal with similar competitive scenarios in the future, I can say that the Thinking Strategically framework will help me to game my company’s competitors; this means to anticipate and pre-empt competitive behaviour.

All three case exercises offered me the possibility to apply the theory. I learned from the three exercises what competing strategically is and to apply what I have learned about Game Theory and Behavioural Insights.

In the first exercise, the group discussion about the pre-emptive life lessons on competition at my previous company, I applied the concept of the Judo Strategy and its strategic principles. My lessons learned from the exercise that I will apply in my career are that using Game Theory and Behavioural Economics can help me avert the difficulties of cognitive blind spots³⁴. The concept of Judo Strategy offers me creative ideas to recognise the threat of the market entry of bus operating companies and to pre-empt the lack of Behavioural Insights into bus competitor’s decision-making abilities to scale their market in the low-budget student target segment.

In the second and the third exercise — deal making and auctions — focused on competing strategically under incomplete information. In the second exercise, the M&A deal making, I used the concept of the Winner’s curse. I have learned from the exercise to take the Winner’s curse into account in my M&A bidding behaviour to prevent my Corporate Strategy group from losing substantial amounts of money. For future M&A transactions, I will apply my lessons learned — to set a limit M&A price and avoid bidding wars. To implement my lessons learned, I will tie my Strategy team to the success of the deal and will lobby in the company to have a dedicated M&A group.

In the third exercise, the English and Dutch auctions, I applied the Bidding strategies. I have learned from the exercises that the English auction type is correctly applied as the right bidding method in the European rail freight corridor tenders because of the highly competitive bids in the for concentration and overcapacity renowned rail freight industry. Consequently, the highest bidder gets the win for the valuation of the second-highest bidder. In addition, my lessons learned from the auctions is that digital consulting projects for my previous employer should continue to be negotiation, instead of auctions. Because the company is not uncertain about the digital consulting company’s side of the transaction and the value to gain is high enough in contrast to the transaction costs, the negotiation would be the better choice.

4. References

[1] Mak, V. (2021) Seminar Thinking Strategically 1/4. Cambridge: University of Cambridge

[2] Oberholzer-Gee, F. and Yao, D. (2004) Game Theory and Business Strategy. HBS case #9–705–471

[3] Camerer, C. F. (2003) Behavioral Game Theory: Experiments in Strategic Interaction. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, p. 31ff

[4] Levine, S.S., Bernard, M. and Nagel, R. (2017), Strategic Intelligence: The Cognitive Capability to Anticipate Competitor Behavior. Strat. Mgmt. J, 38: 2390–2423

[5] Kahneman, D. (2011) Thinking, Fast and Slow. London: Allen Lane, p. 199ff

[6] Oberholzer-Gee, F. and Yao, D. (2004) Game Theory and Business Strategy. HBS case #9–705–471, Yoffie, D. B. and Kwak, M. (2002) “Judo Strategy: 10 Techniques for Beating a Stronger Opponent.” Business Strategy Review, 13(1): pp. 20–30

[7] Corts, K. S. and Freier, D. (2003) Judo in Action. HBS case #9–703–454, p. 4f

[8] Brandenburger, A. M. and Nalebuff, B. J. (1995) “The Right Game: Use Game Theory to Shape Strategy.” Harvard Business Review, 73(4), p. 5ff

[9] Ryall (2013) p. 83ff

[10] Yoffie, D. B. and Kwak, M. (2002) “Judo Strategy: 10 Techniques for Beating a Stronger Opponent.” Business Strategy Review, 13(1): pp. 20–30

[11] Soman, D. (2014) “The Innovator’s Challenge: Understanding the Psychology of Adoption.” Rotman Management, Fall 2014, p. 5ff

[12] Chakravorti, B. (2004) “The New Rules for Bringing Innovations to Market.” Harvard Business Review, 82(3), p. 64f

[13] Capen, Clapp, and Campbell (1971). Journal of Petroleum Technology, 23(6), 641–653

[14] Roll, R. (1986) The Hubris Hypothesis of Corporate Takeovers. The Journal of Business, 59 (2): pp. 197–216

[15] Dixit, A. K., Reiley, D. H. and Skeath, S. (2015) Games of Strategy. 4th ed. London: W. W. Norton, p. 637ff

[16] Thaler, R. H. and Sunstein, C. R. (2009) Nudge: improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. London: Penguin, p. 23ff; Baucells and Weber (2009) p. 30ff

[17] Lovallo, D. et al. (2007) “Deals Without Delusions.” Harvard Business Review, 85(12): pp. 92–99

[18] Ly, K. et al. (2014) “A Practitioner’s Guide to Nudging.” Rotman Management, Winter 2014, p. 29f

[19] Mak, V. (2021) Seminar Thinking Strategically 2/4. Cambridge: University of Cambridge.

[20] Baye, Kovenock, and de Vries (2012) Games & Econ Behavior

[21] Vickrey, W. (1961) Counterspeculation, Auctions, and Competitive Sealed Tenders. Journal of Finance, 16(1), 8–37

[22] Dixit, A. K., Reiley, D. H. and Skeath, S. (2015) Games of Strategy. 4th ed. London: W. W. Norton, p. 639f

[23] Dixit, A. K., Reiley, D. H. and Skeath, S. (2015) Games of Strategy. 4th ed. London: W. W. Norton, p. 639

[24] Mak, V. (2021) Seminar Thinking Strategically 2/4. Cambridge: University of Cambridge

[25] Van Heck, E. (2000) “The Cutting Edge in Auctions.” Harvard Business Review, 78(2), p. 19

[26] Dixit, A. K., Reiley, D. H. and Skeath, S. (2015) Games of Strategy. 4th ed. London: W. W. Norton, p. 640

[27] Basu, K. (2007) “The Traveler’s Dilemma.” Scientific American, 296(June), p. 93ff

[28] Dixit, A. K., Reiley, D. H. and Skeath, S. (2015) Games of Strategy. 4th ed. London: W. W. Norton, ) p. 640

[29] Dixit, A. K. and Nalebuff, B. J. (2008) The Art of Strategy. New York: W. W. Norton, p. 294f

[30] Mak, V. (2021) Seminar Thinking Strategically 2/4. Cambridge: University of Cambridge

[31] Mak, V. (2021) Seminar Thinking Strategically 2/4. Cambridge: University of Cambridge

[32] Subramanian, G. (2009) “Negotiation? Auction? A Deal Maker’s Guide.” Harvard Business Review, 87(12): pp. 101–107

[33] Spann et al. (2018) Customer Needs and Solutions, 5, 121–136

[34] Wason, P.C. (1968) Reasoning about a Rule. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 20(3)

Thanks for reading! Liked the author?

If you’re keen to read more of my Leadership Series writing, you’ll find all articles of this weekly newsletter here.